Thanks for continuing to read my memoir and a special thanks if this is your first time. For first timers, I have a couple of suggestions. There are already three posts about 1995 before this one, and a couple dozen posts about the events leading up to these, beginning in 1992. You can find all the previous posts here on the Substack app, but the easiest way to catch up would be to enter your email to subscribe. You will get a welcome email with all the posts listed in order, and new episodes will be emailed to you directly every Sunday morning.

My mother’s training as a nurse spilled over into the way she ran the household. We three children made hospital corners with our bed sheets and knew the value of protein for breakfast even if we hastily ate the Frosted Brown Sugar PopTarts we preferred as we ran out the door for school. Mom also kept meticulous “nurse’s notes” on our medical histories and her own. That’s how I know that in an otherwise medically unremarkable year in her life in which she recorded no change in her blood pressure, cholesterol levels, or mammogram, on August 5, 1995 she fell down the stairs carrying a load of laundry to the finished basement, breaking the fibula bone and ankle on her right leg. She was taken to Aurora Medical Center and was operated on by Dr Wintory who inserted two pins the following day.

My father could cook one dish for dinner (salami omelet) and had always claimed his colorblindness prevented him from reliably separating darks from lights to do laundry. I flew to Denver to provide moral support, get the house set up, and train Dad for when Mom returned home after rehab. I decided to stay a few days longer to be sure the new systems worked as she would be using a walker to keep weight off the leg for at least two months - longer than they could subsist on omelets and let dirty laundry pile up.

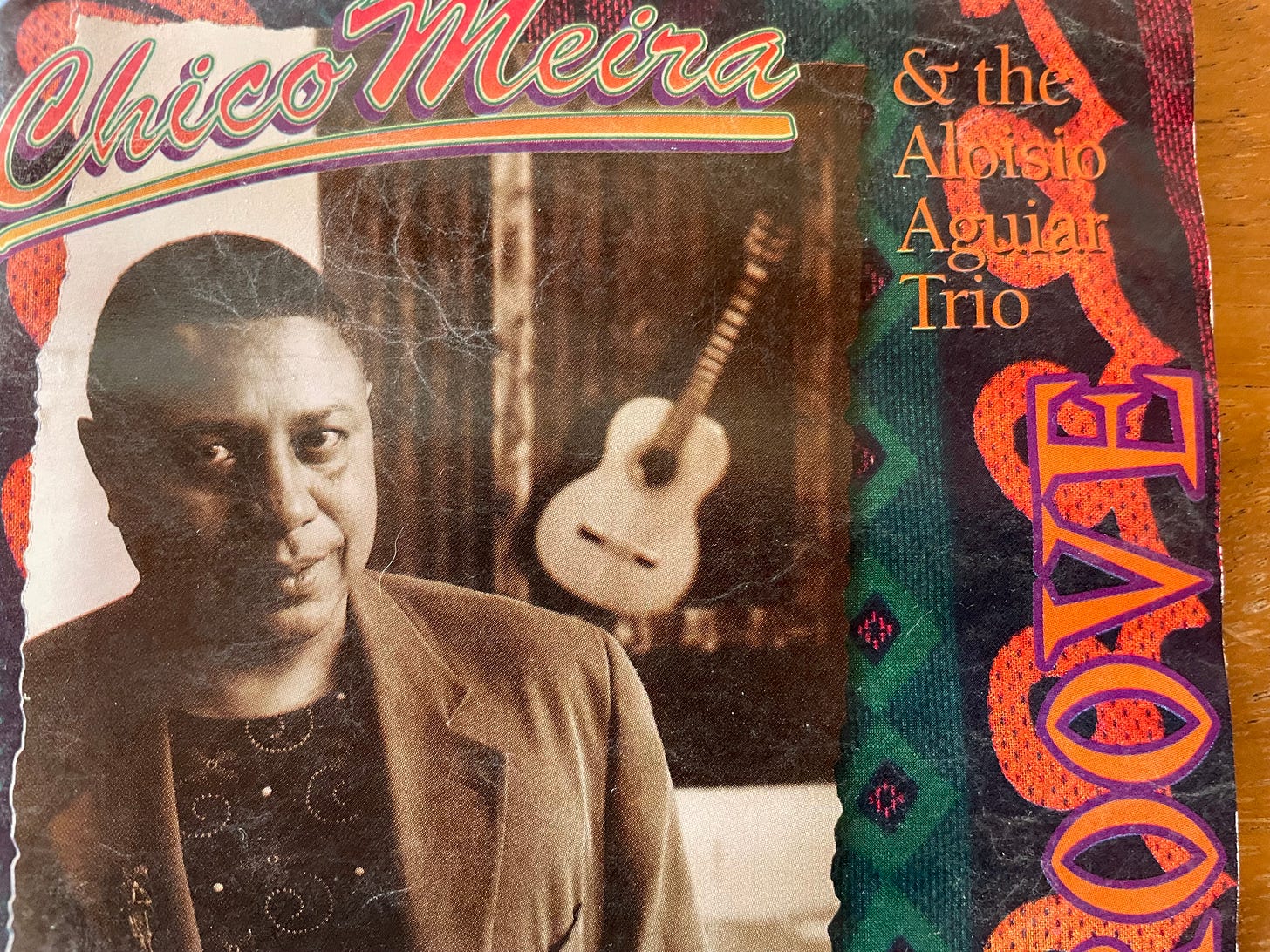

By the time Mom came home, I was desperate for an evening off after almost two weeks of cooking early dinners and watching CSI with Dad. When I noticed in the Friday entertainment section of the newspaper that a local Brazilian group was performing at a jazz club that night, I slipped on a little black dress and sandals with heels, and told them I was going out to enjoy the music. Thanks to years of solo business travel, I never thought twice about taking myself out for an evening.

I found a seat at the bar next to a woman listening attentively to the music. I ordered a glass of Chardonnay and the woman raised her own glass to acknowledge me. She introduced herself and I repeated her name, Cenir, adding, você é brasileira, então? - more a statement than a question. Delighted to discover that I spoke Portuguese and was knowledgeable about Brazilian music, she introduced me to her husband sitting on the other bar stool, and explained that the leader of the group was her brother. I was already assessing her brother. Super cute smile, personable with the audience, and, importantly, more than merely competent on vocals, guitar, and cavaquinho. Yes, he was single. Cenir was not a musician herself, but hosted a Sunday night show on the local public radio station featuring the music of Brazil.

At intermission, Chico joined us. His enthusiasm and ready laughter charmed me. At the end of the evening I was invited to their regular Saturday afternoon gathering of Brazilian friends and family at his house in Boulder to listen to music, drink caipirinhas, maybe help cook up a feijoada or moqueca for the crowd.

It was inevitable. Chico and I quickly became friends over our shared love of Brazilian culture; and then friends with benefits, in the most classic sense. Music was his passion, but he had a good day job at one of the tech manufacturing firms. He was also a loving dad to a beautiful young daughter, and Juliana’s mother was staying in the Boulder area, so he was committed to staying there too. Moving back to Colorado was not in my plans; leaving was not in his. Neither of us was thinking of exclusivity or a long term future, but I was happy to spend weekends in Boulder during my regular visits to my parents during my mom’s many months of recovery, and Chico was even happier to visit me in New York City.

Chico and his daughter at a country fair we attended in Boulder, 1995.

Our long distance relationship lasted almost to the end of 1996. I traveled a lot that year, and so was not dating anyone else, but Chico was seeing a woman he had been dating off and on. His daughter liked this woman and so did he; his only hesitation was that she showed no interest in learning Portuguese, did not like Brazilian food or feel comfortable hanging out with a crowd that came together so the music, food and language would transport them home for a few hours. She was not even excited about attending his gigs. Still, eventually he called to tell me that his sister was urging him to break off his relationship with me. She thought this woman was a catch as her family was in Boulder and she was stable and sweet. As long as Chico was also seeing me, he might never commit to her.

(Imagine the following conversation in Portuguese). “Cenir has a point,” I allowed. “Maybe if you committed to this woman, she would make the extra effort to embrace your identity as a Brazilian. After all, she would have to talk to your parents at the wedding!” I joked. I continued, “As your friend, my only question is whether you love her.”

The phone line was silent for a very long pause.

“I guess I love her enough,” was his answer.

“Then itʻs decided,” I concluded. It was clear to me that we could not even continue as just friends without the benefits. She was an all-American girl and the way close friends express themselves in a more relational culture would always run the risk of triggering her suspicions. The most loving thing I could do for my friend was to bow out gracefully so their love and commitment could grow.

There is a Portuguese word that has no exact one-word translation in English: saudades. Saudades is like homesickness, a longing or missing for a place or a person or a time or really a combination of these that opens the heart to both feelings of sadness at not being there/together, and even more so a kind of melancholic joy at the very existence of that fondly remembered place/person/time.

When you do something like gathering with other expatriate Brazilians to share music, food, and conversation, you are matando saudades, literally “killing” the saudades. Chico and I were also matando saudades with our liaison. Both of us knew at some level that we were leaving our history with Brazil behind. He would always be carioca but his relationship with his homeland would change. And if Brazil was my transitional relationship out of my settled life measured by achievement, Chico was my transitional relationship to let go of my transitional relationship with Brazil.

But this is foreshadowing. The year 1996 is still ahead in this memoir and it was a year full of adventures, some of which continued to bring me to Boulder for weekends with samba and pão de queijo. Colorado turned into the way station as I gradually worked my way west to that other pais tropical, the tropical country that perhaps Brasil was preparing me for all along.