As I explained in What Happened Before Tibet Happened, Vijali (who used the Tibetan name sheʻd been given, Dorje Dolma, during our time in Tibet) chose Shoto Terdrom as one of 12 sites on the first World Wheel because it is a place associated with Yeshe Tsogyal, a place where she and Padmasabhava (also known as Guru Rinpoche), the master teacher who brought Buddhism to Tibet, lived and practiced as consorts in the 8th century. Together they concealed “treasures” of spiritual knowledge, some of them in this very valley.

Beyond the value of Yeshe Tsogyal as a historical figure serving as role model for women seeking spiritual mastery in the Buddhist tradition, she is believed to be walking among us today. Before leaving her physical body in the manner reflected in Vijaliʻs cave art in Shoto Terdrom, she promised to respond to prayers, to appear in dreams to guide practitioners, and to continue to send “emanations”, living women who share the same mind stream (as opposed to being an incarnation, having shared past embodied lives).

And, as with hindsight I seek to make connections with my intuitive understanding that my offer of service to White Buffalo Calf Pipe Woman had brought me to Tibet, I see this possible connection between the two. Pte Sa Wi also taught her people at the time she lived with them, and promised to continue to be present for future generations as they filled their pipes and performed the ceremonies she taught them. At this critical junction for humanity, we have witnessed the birth of white buffalo calves to remind us of her message of harmony and care for the earth. A Tibetan might say she is sending emanations.

Here are the entries from my time in Shoto Terdrom, central Tibet.

May 26, 1992

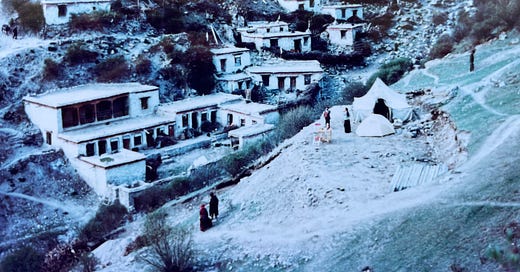

It is about four in the afternoon and the sun is momentarily intense. It rained and snowed throughout the night and on and off all day. Now the clouds have broken and the sun is bright as mid-summer. I am sitting in front of my Tadpole tent, surrounded by strings of prayer flags and bushes festooned with bits of animal fur. This mid-hill point overlooks the stream, the ani gompa (convent), and the lower flat place where the cooking tent is pitched. The valley is difficult to describe. We are higher than in Lhasa, 16,000 feet above sea level, yet it feels milder here, and wildflowers are blooming. At this point the valley is quite narrow, and twists so that we are surrounded by rocky hills rising steeply in all four directions, although the river canyon is oriented north-south.

This morning I awoke to a hallucination – the smell of burning cedar. Must be a very raw kind of Tibetan incense, I mused. I emerged from my tent to discover a nun tending a fire not 15 feet away, and on it she had placed whole branches of cedar. Many nuns and monks were beginning the kora (circumambulation) route around the valley, this being a Guru Rinpoche special day on the Tibetan monthly calendar. I pulled a small baggie of cedar from my pouch; we compared it. She nodded and gestured; I added mine to the fire.

Breakfast brought a difficult scene. Karil reacted fearfully to the falling snow and remoteness, objecting to the planned return of our driver to Lhasa until we required him to collect us in eight days. We tried to reassure her that there are lots of people and vehicles coming and going, and even animals her for transport if anything goes wrong. As Karil insisted, Dorje Dolma explained again that she is struggling with her sense that this no longer feels like her World Wheel, because we are traveling according to Karilʻs need for comfort and her modus operandi. Even our living arrangements have been compromised. Karilʻs big tent was supposed to accommodate her, Dorje Dolma, and all the gear. I came with a one-person backpacking tent, which Dorje Dolma and I are now sharing as Karil found she needs all the space in hers. I express that I didnʻt come to Tibet to be a part of Karilʻs film. It feels disturbing to me when we fail to move softly and meet the people and places on their own terms. We have been discussing this together for several days now, all three of us locked into our same views. I notice the arguments are the same, the behavior has not changed, but our tone is a bit warmer as we seek to harmonize. How will this play out?

After breakfast, Dorje Dolma and I had planned to find the hot springs to wash, but she suddenly felt tired. I notice two nuns, just girls, walking with an elder nun, and started walking with them. We complete the kora in about an hour, passing down and across the river on the ridge where Guru Rinpoche threw his vajra, up to the prayer flags on the opposite side, picking a way down again through rocks spelling out mantra on the hillside, to a small shrine upstream, back around the stupa and the assembly hall. With the other two in the tents, I have the solitude I craved for today to make my own inner connection with Shoto Terdrom and its people.

May 27, 1992

Our table was set for breakfast outside in anticipation of the sun that would bless this day after the snow had blessed the night. We ate delicious porridge and eggs, watching three monks pass, doing the kora with full prostrations. Just as we were discussing how later in the day we would find a senior nun to ask Dorje Dolma's three questions and begin filming, three wizened old ani came by to inspect us. Now we are set. Emeril is translating on the right side of the semi-circle as Dorje Dolma asks questions on the left. Karil is filming with the ani gompa as a backdrop. Checkov and I sit quietly on rocks to the side.

These three explain that they have been here since adolescence. Their ages are 69, 76, and 89. After 1959, they were forced to hide in their villages to wait out the Cultural Revolution. Their concerns are simple, not global: a harsh environment and not enough to eat. They never stop smiling. Not during the interview, and not during the rest of the day. Whenever they pass our tents they stop to "chat", miming everything from Dorje Dolma sleeping, to the dogs growling and tussling nearby.

After the interview, we walked up the canyon to the east of us, to see if there is a site for Dorje Dolma's work. The canyon bends gently at a suddenly secluded, enfolding spot. There is a trickle of a stream, cliffs rising but not too imposingly, thickets of red willow bursting with fuzzy pussy willow blossom, tiny white and purple flowers, orange and yellow lichen, green mosses, ferns and nettles. We watch the huge crows and tiny butterflies. Dorje Dolma is drawn to a small ledge about five feet up. She and I meditate there, our backs against the limestone.

After lunch, we sit at our table in the sun. Dorje Dolma wants to look in two more directions – to the south past the kora route, and along the parallel canyon to the west of where we walked this morning. Dorje Dolma shares her tentative idea for her project here. She envisions a figure in a cave, seated in meditation. Her concerns are how she will handle the limitations here: little time to sculpt, and little ability to involve the nuns without putting them in jeopardy with the authorities. She worries that her art might have meaning and impact for us as Westerners, but not being traditional it might not touch people living here or might even seem sacrilegious to them. Karil interjects that what she relates to in Dorje Dolmaʻs work is the "motivational aspect,” by which she means that she sees Vijaliʻs work as changing the community or inspiring people to be different. She is concerned she does not see how that will be achieved with what Dorje Dolma described.

Immediately, words come through me, but I choke with emotion as I try to voice them. I explain that over the last year I had come to the profoundly experienced belief – not intellectual understanding - that one knows certain actions or rituals have impact in the world in profound ways that are real even if impenetrable to logic. As Karil starts to argue, I am overwhelmed by the energy flow inside and outside of me. My voice turns husky trying to describe what I am experiencing. Finally I just say that I didn't need a rational answer to these questions because I was getting the answer in my body at that very moment. I look over at Dorje Dolma, but she had spontaneously entered a state of deep meditation or trance. I try to keep my eyes open politely as Karil continues to talk, but have to turn to look down the valley.

Later in the tent waiting out a wind-hail-snow storm, we reflect on what had happened. Dorje Dolma said, this is why Yeshe Tsogyel and her consorts came to this place--because it exists as a power place where they could deepen their practice. It is not the other way around, that this became sacred because they were once here. The same is true for us. The impact our being here has on the world is whatever we carry away with us, to New York or to the next countries on the World Wheel, and what we make of the internal and external experience of having been here.

Each day brings richer connection. Terdrom is speaking to us directly, and her language needs little translation.

May 28, 1992

It was gray and cold this morning, a good day for a hike. Emeril suggested either the top of the ridge or the Guru Rimpoche cave. Dorje Dolma wanted to go to the cave as well, so it was agreed. Besides hiking, she had other objectives for the day: to locate the Khadro and her helper, the man who had house and fed Tsultrim and her group, in order to deliver photos from Tsultrim; and to finalize the selection of a site for her sculpture.

We climb a steep trail for an hour, passing a large complex of buildings on a higher plateau. We look back down, gasping for breath, noticing how the canyon over which we're camped is etched deeply in a much broader valley formed by the higher peaks. Two nuns join us for the last pitch, retrieving a woolen glove Dorje Dolma dropped on the way. In front of the cave are small buildings stacked upon one another; we approach these, clamber up rocks--and there is the cave! And--there is our man! I had forgotten that this was the place Doltse lives, but I somehow recognize him immediately. He begins to make the motions of drum and bell with his hands, as he tells Emeril in Tibetan that some American women visited him last year. We excitedly explain that we are friends of those women, and pull out the pictures. He invites us into a lovely, simple two-room building, where we sit on low benches, admiring a large prayer-wheel in the center of the room, and 1986 calendars on the walls. Over many cups of butter tea served by our gap- toothed friend, we tell stories and ask questions.

Finally, Dorje Dolma and I ask to go below to the gompa to meditate. It is a very still and powerful place, and our meditation is long and deep. We don't want to leave, even though it is so cold we are wearing hats, gloves, and down jackets. Finally, we rejoin the two upstairs, who are still conversing in what we now learn is actually Khadro's room. She is in Lhasa, but will return in a few days. Dorje Dolma thinks hard. She wants to come back here; she needs all the available time to complete a sculpture. We can see the canyon we explored yesterday from the small window behind us. Is there a path into it? Yes! We can do both. But first we must help give medicine to a sick yak that was left yesterday by a monk who arrived doing full prostrations.

Finally we descend on a trail that is actually shorter than the way we climbed. Our guide shows no hesitation in crossing the snow field which stopped us yesterday. Just beyond, Dorje Dolma finds a beautiful cave with stalactite-like pieces of rock studding the ceiling. She climbs into it, explaining to us that she envisions the outline of a boddhisatva, which she would paint as a rainbow body. People could come here to sit with their back to the outline and meditate on this expression of the Buddha within each of us. Emeril thinks this is fine, no permission is required.

I am reminded that Doltse has just instructed us, if we return to the Guru Rimpoche cave, to meditate with our backs touching the stone. This was precisely what we had done spontaneously on the ledge yesterday that generated such a powerful connection, and Dorje Dolma's vision of her piece. To me, this the confirmation that what she plans to do is right.

We reach camp in about 10 minutes of downhill walking, in time for a late lunch in the sun and wonderful long baths in the hot springs.

May 29, 1992

The day broke cloudless and the sun crested the eastern ridge as we breakfasted, a fine day to begin work. We pack tools and lunch, and walk to the cave. Checkov arrives just as we ready ourselves for an opening ritual. He agrees to participate; Karil films. I light sage and cedar, handing it to Dorje Dolma to smudge the cave, acknowledging the seven directions. She asks the spirit of the cave for permission, pledging that she will do nothing to harm or change it, only to bring out the spirit as it exists. She hands the pot to me, and I pray for us to experience an inner connection with this land and people that may be mirrored in the outer world. Checkov adds his prayer in Tibetan. We join hands and smile.

The first task is to knock down any dangerous rocks overhead. Then we don gloves and clear the cave floor of debris, down to a rich-smelling dirt. In the process, we discover a mani tablet! Checkov translates: it is om ah hung benza guru pedma siddhi hung. Dorje Dolma and I have both been taught this mantra and we will recite it as we work. Below the cave is a second inscribed stone, which we move to the altar we have created above. With the rubble we make steps and outline the entrance. Dorje Dolma has Chekov sit in meditation pose, and draws his outline on the back of the cave. He asks if his job is done, and returns to camp.

Work starts at the cave. Photo credit: Karil Daniels

We break to feast on boiled potatoes, hard-cooked eggs, and oranges.

I climb both sides of the canyon after lunch. The immediate path on the western side leads up to the flat grazing field below the large compound we passed yesterday. I sit facing south to meditate. I hear puppies barking and open my eyes a slit. Three of them tumble on me. The young nun with them sits patiently watching me for the next twenty minutes. “Dalai Lama kupaa?”

I trace the ridge to the north, dropping down along the path we traveled yesterday and back to the cave. Dorje Dolma tells me the rock is quite hard, her carving tools are inadequate, so there will be more surface image, less depth. We both feel just the creation of the space itself is significant; we also agree it is calling for a more feminine element, represented by the figure. I leave again to climb the eastern face, which leads steeply and directly to the retreat house which has not been restored. It is perched on a knob, the rock dropping steeply to all sides. Spectacular!

Returning to the site, I do my daily mantra, watching as the sun dips over the canyon wall and a chilly wind sweeps up the canyon. Dorje Dolma is engrossed in her work, an organic, non-linear process of color, outline, carving all proceeding together so that an image grows almost like cells dividing to create definition.

Chilled enough to return for tea, I overtake Karil on her return walk. I donʻt know what to say to her. She has taken no joy today in this beautiful, intimate canyon, nor in the stream emerging at our feet that gurgles down mosaic-colored rock formations, nor in the lichen, willow and wildflowers, nor in the blue sky and wispy cotton clouds. She hid under an umbrella, ate only a chocolate bar, complained of her headache and upset stomach. I am at a loss as to how to introduce her to my experience. It is as though we torture her by being here. I wonder how her film can express how we glory in this place, how being here, touching earth, clearing a space, arranging stones as they ask, how all this is sacred creation and in each moment we are forming the World Wheel. I am filled with gratitude for being allowed to share this experience with Dorje Dolma, and just rest quietly in that.

Down at the hot springs there is a snake. I wonder is it a water spirit? The old nun who bathes nude every afternoon at this time patiently moves all our clothes around away from the snake until it leaves. It returns as I dress and all of us quickly move ourselves around! Later our guide assures me it is harmless, and it felt so.

I spell the boys on kitchen duty, adding to Chinese noodles a can of tuna and mushroom soup mix purchased in Nepal, some onion and almonds, to create a tuna-noodle casserole that gets rave reviews. I like to feel like family, but I wonder what they really think of us. Maybe thatʻs overcomplicating it, and there are no hidden feelings, just exactly what's on the surface, on the levels of the group, and individual, relationships. On one level, we must be a fun group because we donʻt want the standard tourist tour and I like to believe we are interacting differently than the usual group, with them and the other Tibetans we meet. And then there are individual moments of connection or moments of difficulty.

There is also the level Emeril expressed eloquently in terms of the Six Realms. You Americans live in the God Realm, he said, with all your material comforts. But I don't envy you, there is sadness in your heart. We Tibetans are only in the Human Realm, and we suffer basic wants, live simply, donʻt know sophisticated things, but we are happy in our lives.

Maybe he is right, thatʻs the best way to look at it, we fundamentally still live in different realms. I love their sense of humor and the ease of their relationships with one another, including physical touching between the three men. The nuns too are an intriguing combination of shyness and boldness. They giggle and hide from our cameras and questions, but will come up to peer boldly into our tent without invitation, or touch their heads against ours to share a laugh. How wonderful to live here, to make kora and butter tea each day.

May 30, 1992

Dorje Dolma headed straight for her site, Karil lingered in camp, so I decide to hike up the valley to the west, in which direction Emeril told me I would find a monastery two hours away. What a walk! The rock formations on either side are spectacular, volcanic, dramatic, ever-changing. The path crossed back and forth over the river on exquisitely constructed bridges of stone foundations and planks. Along the trail were cairns, and particularly beautiful rocks set carefully in niches or atop large boulders, to honor the spirits. In one place a quartz vein had left shimmering shards. I collect handfuls to take to the sculpture site, and to take home as gifts.

In 2-1/4 hours I see only two child-monks, and three nuns. The monastery finally reveals itself, the valley opening guarded by an enormous phallic natural stone pillar. I stay in the clearing by the prayer wheel, looking up at the main buildings. They remind me of Taos pueblo, set in the hillside, the upper entrances reached by ladders. Trumpets blow as I munch on a granola bar.

I get back to camp exhausted, and almost unable to speak, laryngitis being the newest symptom of the upper respiratory ailment to which I finally succumbed. This is worrisome, because Emeril has located a lama who agreed to teach two tourists the Chod, and he is expected this evening. In the meantime, our ani friends appear with cord to restring our prayer beads. Mine is first, the beads held in Dorje Dolma's lap, the head nun stringing from one end, our driver Hoke coming over to help string from the other end. I will treasure these beads, strung with such care.

Our lama is spectacular, and we can't take our eyes off him, a slim 37-year-old of pure, magnetic smile. He is a wandering ascetic who will accept nothing from us for the teachings. Together we parade down to the assembly hall, with both our guides, all the nuns, and even the German tourists who set up camp for the night. There is much laughter at our efforts with bells and drums. Then he performs a beautiful long version of the Khandro Chod, gives us complicated instructions for a retreat of 108 days, and scriptures to study. There was something quite miraculous in his having agreed to this, and we felt as though we had indeed received initiation. Now find a good lama at home, he insisted.

May 31, 1992

Today, I spend the whole day helping Dorje Dolma. First I work on my "sculpture", a patch of ice into which I am carving the sun-moon sign the Tibetans paint on their doors. I get to use the chisels and hammer we bought in Lhasa. I walk back to the camp to bring lunch, Chod bags, and Karil to the site. After a bit Karil returns to camp; Dorje Dolma and I take a break to practice Chod, then I fit in a half-hour hike while she meditates.

Dorje Dolma's sculpture is taking beautiful form, a Chod image, mind flying out the crown chakra from the rainbow body. We excavate the figure's crossed legs in the floor of the cave, mounding the rich red clay into an outlining lip. While she finishes this, I tidy the sides, level the floor, and clean the mani stones, arranging candles and incense on top. It is a space like a meditation room, and I feel certain it will be understood and used.

Karil has decided to return home when I do, which seems a wise choice as she is continuously miserable. She wants to rejoin Dorje Dolma in China towards the end, but will she be any less unhappy with extreme heat and lots of insects? Plus she will be without the luxury of a support crew. As it is, Hoke now teases me by making grunting yak noises when he sees me carrying Karilʻs gear for her.

June 1, 1992

We got a late start—suddenly at breakfast Doltse appears in camp. Khadro is at the road above, leaving for her prayer wheel. We rush up the hill to bring her photographs. She holds our hands tightly and grins at us, long hair swept into an impish ponytail at the nape. Shoes and warm boots are the biggest needs of the nuns, she responds when we ask. I give her my running shoes on the spot.

I had offered to try to find the cedar Dorje Dolma wants to burn during the ceremony tomorrow, and turn to that task next. I'd awakened in a very still state, setting an intention to walk the day in a sacred manner, conscious with a tearful sadness that our remaining time at Terdrom was short. I want to collect the incense correctly, so ask for the cedar to show itself. I am taken directly to it. I gather carefully, asking permission, offering cornmeal and thanks, taking only what we needed.

I find Dorje Dolma at the site, and turn to the triptych that is developing on "my side". I want her to have the final word, but she insists that this part is mine, and my artistic vision should prevail. It is hard work, moving stones, carving ice.

We rest in the sun and share a little lunch. I ask what is left for me to help with. There are two things – to arrange all the stone leading up to the cave, and to finish the smoothing of the base with water. We sculpt the red clay together, taking water from the stream to soften it, until with hammer and hands we have formed a satiny surface. These tasks complete, it feels right to leave Dorje Dolma to her coloring, completing the fantastic image with shimmering eye shadows. I am startled at how each day the figure has become more feminine. It is at once more clearly defined, the rocks forming knee and breast; and more ephemeral, the surface colors so translucent, the outline so subtle in the way it emerges from the cave wall.

I had wanted to sit on the pinnacle beyond our tents that overlooks the stream and the kora circuit. This is my place for meditation and morning prayers. Here I feel as if I am actually in the canyon, in the totality of the flow of energy and activity. First though, I stop at the kitchen camp for something to drink.

Checkov and Emeril are at the table outside and insist I sit between them. The warmth between us has grown to where it seems they treat me with the same humor and affection they offer to one another. We sit joking for a while. Karil is in the tent, and I go in and out of the tent several times, responding to her requests. I hand her the jacket at her feet, pour her water. Whispering, she asks if I can “wheedle” the remaining toilet paper out of the guys; it disappeared after she took some this morning. Checkov appears at that point and claims to know nothing.

When I return to the table outside, for the first time the guys openly vent their frustrations at how they perceive Karil to be treating them. They ask if I donʻt object myself to what they see as a similar pattern of interaction. Thatʻs why they started calling me “yak,” but now they joke that I am probably the reincarnation of a sherpa because I cook as well as haul for Karil. Humor relieves the frustration. Then the toilet paper reappears.

I return to the tent feeling despondent. I do my mantra. Dorje Dolma joins me in about an hour. We are posting a stakeout, in case the lama Perna Somdup passes by as he did yesterday on kora. I tell her what happened; she suggests I share with Karil how the guys are feeling and why.

We decide our lama isnʻt coming by, then we realize today is our last chance to find him, thank him again, tell him what we are doing here. We rush down to Emeril, who agrees to our precipitous request to walk to the place where the lama is staying. It is a steep hike up the side canyon, above where the road ends, towards a beautiful bowl that lies hidden from the valley. A nun meets us at the house, but she is in silence, and cannot explain. We look in at the small corner of the porch, containing a mat and a low chest, but no lama.

The nun next door explains that Pema Somdup left to help another monk who was moving between caves, and that if he had returned he would be spending the night at the guest house below. We retrace our steps down the slope, and into the courtyard, where one of our elderly ani friends presses her head against mine in greeting. Our lama is inside, drinking milk, exhausted from his day. He listens to Emerilʻs translations of our gratitude and explanations. He nods and reaches into a pouch, withdraws a vial of holy water, and gives some to each of us. He calls to the nun, who brings a sheet of parchment. Cutting this into three parts, then taking out another pouch, he carefully rolls sacred earth which he has prepared into a packet for each of us. We leave our beautiful friend to rest.

June 2, 1992

This trip is so much about releasing expectations and my habit of planning; accepting limitations; acknowledging what is at the moment. It is almost 1 pm on our last day at Terdrom. We had planned to be having lunch after the ceremony by now; instead we have yet to finish preparations.

Short time in Tibet, shorter still at Terdrom, days to find site, so limited time for creation. Result: a piece which conveys what it intends as much because of its ephemeral quality as because of form or color. The figure dissolving into Body of Light, the integrity of background rock and "sculpture", the echo of the sacred, revered imprints which are but barely discernable outlines of body, hand or hoof. Limitations become transformed into meanings.

Impossible to create a performance or ceremony with our whole Tibetan family of guides, nuns, and monks, as this would be seen as political activity, putting them at risk for punishment by the authorities. So the ritual must be ours, for us and the video camera, and the sculpture-cave a place for others to discover for their own ritual, meditation or amusement. But perhaps as future visitors reach this spot, they too will see how the cave bridges the traditional images inside the gompa with the deeply lived understanding these ani have begun to teach us as we share a few days of their lives. The cave is about personal experience.

For me there is also the puzzle of physical limitations, after a sleepless night unable to breathe through a congested nose. Where are the long hard days of trekking? My muscles are taut beneath my long dress, my gimpy left knee attests to plenty of downhill walking. But the trip is not about exercise, as I had once envisioned my “trek to the Himalayas”.

It is sometimes about solitude, and finding it in the middle of a circus sideshow featuring our group as the prime attraction. Finding it exists even with two people together in a tent so narrow and short we cannot sit side by side when we meditate.

We reach the site at about 2pm. Emeril and Hoke come along, but Checkov stays in his tent, feeling sick from too much beer or a passing bug. The men take twigs and wedge them into the rocks to hang prayer flags above the entrance. Meanwhile, Dorje Dolma and I light the cedar. The four of us sit in the cave. Dorje Dolma prays to the Directions. Then she passes around a stone which the Dalai Lama blessed, asking each of us to offer a prayer. She adds Tibetan dirt to her jar. For the benefit of the film, she explains the treasure capsule, which contains some of the mixed earth of the other sites, along with a parchment. I read the Dakini poem I wrote, which I had copied onto the parchment and Dorje Dolma had illustrated in water color. Emeril buries the capsule, along with the Dalai Lama stone.

At this point, Karil checks the camera, discovering that all of the film is flawed. We must stop and make a trip to camp for more equipment. And there is only one person who can make a fast enough trip to camp for the spare cartridges, so I take off. Back at the tent, an intuition tells me to read the manual. The “X” sign means dirty heads, so I throw in the cleaning cassette. That turns out to be the problem, so after a few minutes we can continue.

We restage the entire ceremony, concluding with a brief meditation for the camera. Dorje Dolma wants to stay to take some still photos, while the rest of us return to camp to prepare a very late lunch. Emeril has vegetables cooking and had already made rice. I throw together a stir fry using the last can of tuna, some cabbage, raisons and nuts. There is also soup, a real feast.

An hour later, Dorje Dolma appears in camp, elated. Just after we left, two nuns, young women in their 20's, walked by. They were moved to tears by her work, prostrated and sang chants, then led her to their house to offer treats of yak cheese and sweets. We were all so happy that Dorje Dolma had been given the gift of witnessing this, that those for whom she made it will respond with understanding and joy to her creation.

After our feast, I walk up to my pinnacle, where I am inspired by the sight of the evening pilgrims. I return to the kitchen tent to issue an invitation to the others, when Dorje Dolma's new friends appear, with two wild-looking young men in tow. They plan to do kora with these boys from Kham, long braids wrapped with twists of red silk cord, long knives at their waists. I'd had an elder nun in mind, not a bunch of 25-year-olds, but these were obviously to be my companions.

We don't take the gentle lower path, but clamber up the rock over the river. This is a blessing, for the sacred images lie above. First we look up a narrow opening at a very dark, well-defined image of Guru Rinpoche and touch our heads to the rock. We rub our palms over a footprint. We prostrate three times in front of a cave. We climb up the rock chimney as Iʻd seen others do from my meditation perch. I had not seen what was beyond: a narrow, claustrophobic channel through which we were expected to wedge ourselves sideways, then eight feet into it hoist ourselves vertically through an opening of no greater width. The young men had to remove headwraps and belts to make themselves thin enough. The ani hold these and the jacket Iʻd carried around my waist, climbing over the top to meet us.

We rest, panting, on the other side. They give me a thumbs up sign, laughing and affirming in English, “Buddhist!” From there we continue at breakneck speed, but at least they take the inner kora route, soon reaching the stupa. Dorje Dolma had begged off by placing her two hands to one side of her head and closing her eyes to indicate sleep. One nun now repeats this gesture and points toward the tent, looking at me with a bright question in her eyes. I touch her shoulder and nod. We walk together up to the campsite. Peering into our tiny tent, miming disbelief that the two of us occupy the sleeping bags wedged side by side.

Yes, we really both sleep in there. Lucky we are petite!

Soon Hoke appears, a big surprise, on his way along the kora in street shoes. I jump up to join him. Little did I know our stocky driver was into "aerobic kora”. I literally run after him until his first rest at the top of the opposite side. Thankfully, he too chooses the shorter lower path. Completing the circuit, we both grab towels at the kitchen tent for a sunset soak in the hot springs.

This proved to be a popular idea...the womenʻs side was full. As I ease into the water, a gap-toothed ani paddles over and asks me “Dalai lama kupaa?” For a moment I freeze, puzzled, wondering how she thinks I could honor her request. Then I get the joke. I pretend to extract one from my drenched swimsuit and ceremoniously hand it to her. She examines the phantom photo carefully, holds it to her head, then turns cackling to “show” it to the other nuns. We pass around soap, and I wish that like them I swim nude. But I had been cautioned to be mindful of the Chinese workers who peer down at us from their work site above.

Blissfully warm and relaxed, I make my way back to the kitchen tent in search of water to quench my serious thirst. Emeril is making chapati. Chekov, fully recovered, sits grinning at the back of the tent with Hoke. They make a place for me. Alas! No boiled water in the thermos, and my water bottle is empty. No choice but to accept the beer Emeril offers. As the light fades from the sky, we sit in companionable raucousness, teasing and singing. We have shared nine days in a very special place, revealed ourselves, accepted one another. With the last light fading against the outline of dark mountains, I climb to my sleeping bag for one last night in Terdrom.

June 3, 1992 - Lhasa

This morning those icy bits of snow were falling from patches of clear sky. Instead of sitting meditation with Dorje Dolma in the tent, I opt to pull on my jacket for one last kora. The sun cuts through by the time I rest on the facing hill. It feels so easy today. I check my heart rate. After little more than a week of this, my exercising heart rate is 120 beats per minute, same as at sea level! I double check, get the same result. Moving steadily I find myself back at the stupa in 40 minutes, two-thirds of the time of the first day. Check the box on trekking in the Himalayas.

I decide to begin my daily mantra commitment as I circumambulate the stupa. Each elder ani going to and from the river meets my eyes, acknowledging me. I think I must remember to look in the eyes of every human being I meet, every day, and acknowledge them that fully with the meeting of eyes. Then I think: what would it be like at work if I do this? I push the thought away.

Our friend the head nun comes by. She touches my chest and asks “Ming la?” “Beth,” I reply. She holds her fist on top of her head, indicating the way in which Dorje Dolma has worn her hair. “Dorje Dolma,” I answer. She repeats our names, nods, smiles.

By 9 am I am at the kitchen tent. The guys pour me butter tea – our secret ritual, a shared cup of their tea each morning before the other two women descend. I set the table, put out the biscuits and chapati. Emeril cooks an egg for each of us. This is also our ritual.

After breakfast I pack before a helpful audience of a half dozen nuns. They zip bags for me, and carry them to the truck. Dorje Dolma and I race back to the sculpture to try to get good photos in the brighter morning light. We honestly need the photos, but mainly it is good to see Her one last time. The two who visited yesterday share the last house on the path to the cave. They have appointed themselves guardians, and join us, carrying Dorje Dolmaʻs bag and jacket. Then up to the trucks, last Dalai Lama photos handed out, last waves – and we are off.

I fall into a testy silence. I suddenly feel caged, upset to be separated by metal and glass from this land I have come to love. Karil perks up – announces she finally feels almost like herself. She chatters on about the landscape, animals, greenery we pass, somehow finally relating to this environment.

When we stop for lunch in town, Dorje Dolma and I veto the Chinese restaurant so the whole crew crowds around tables for Tibetan noodle soup as dust flies in the open doorway, settling on my cup of hot water and sinking to the bottom. I adore the soup, freshly cut thick strips of wheat noodles, then cellophane noodles, and a few bits of yak meat and greens, all in a rich, spicy meat broth.

At the hotel I take a hot bath and wash my hair, finally getting the dirt out from underneath my nails. It feels good, but I miss the hot springs, bathing communally with the firmament above! I will miss chanting through morning chores, making a kora, doing hard honest work with my hands, all in constant intimacy with the beautiful land and all its elements. No wonder the Tibetans have five. Yes, there is earth, air, fire, and water here – but the overwhelming sensory impression is of space. Can this sense of spaciousness be the ground for me wherever I am? If I could take this sense of space back with me, and the habit of a moment of pause before opening my mouth to speak, and the gift of acknowledging each human being truly in that very moment – these would be the foundation of a different way of being in the world. A wiser, kinder, more loving, better serving way of being.

So what is next for me? Is it more intensive study in one tradition? Dorje Dolma likes Dzogchen, the idea that we are already “there” and can attain instant Enlightenment. There is much in the practice of sitting meditation and the teachings on the nature of mind that I am finding valuable. And yet spiritual practice for me is so bound to the physical world of creation, which is why I first opened up spiritually sitting in a lodge of willow singing to the Sky. Small wonder this woman Dorje Dolma/Vijali was to be my mentor on a pilgrimage to Tibet, she who lives in caves and trailers and sculpts the earth.

Then there is Oh Shinnah Fast Wolf, how did I come to be buying a house with her and Cynthia, linked in a practical way. Whatever evolves as student/teacher we are becoming relatives in the Native sense. Where do I fit in this pantheon of women in whose company I so suddenly, in the space of half a year, find myself? Not just as a devoted student taking seminars year after year. I meet these women and we move in together. Iʻm buying a house with them, or sleeping side by side and meditating knee to knee in a tight tent pitched in Paradise.

Itʻs 10 pm and I have been reflecting and writing for more than four hours, trying to record and maybe begin to integrate these precious days. Tomorrow I will have to cope with the process of re-entry, gradually building through Chengdu and Hong Kong back to the world I left behind four weeks ago. The challenge will be to remain open. Who knows whether the pilgrimage is finished? Perhaps the best is yet to come? Perhaps I just keep walking it...