What Happened Before What Happens Happens #1

Context for the events and transformation that came in my mid-30s

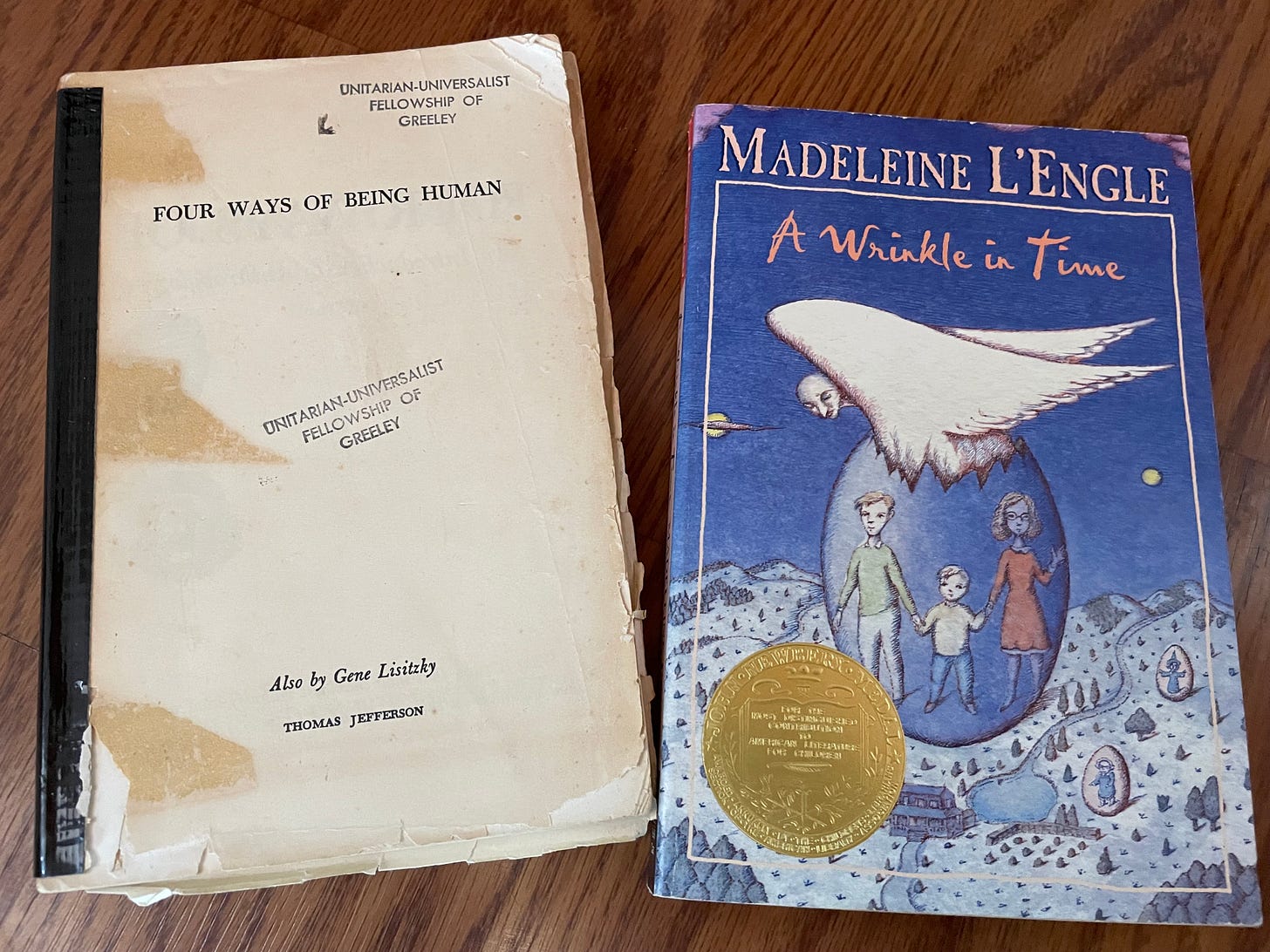

When I was in fifth grade, I stole a book. Even worse, I stole it from my Sunday school. I was a child who followed the rules, but I broke them this time because I could not bear to go on in life without this book. Today its front cover is missing, reminding me with two stamps that it belongs to the Unitarian-Universalist Fellowship of Greeley. It was not a religious book, at least not in the conventional sense. Its title: Four Ways of Being Human.

The essential book of my childhood is a young readerʻs introduction to cultural anthropology. In the authorʻs note, journalist Gene Lisitzky describes her desire to write about anthropology as “the perfect educational tool it is - a mind stretcher, prejudice dissolver, and taste widener.” Some of the language today shows up as cringeworthy, starting with labeling the four cultures as “primitive.” What stuck with me as important, even at that early age, was Lisitzkyʻs exhortation that “primitive cultures seem insignificant today only because we see them as tiny remnants struggling hopelessly to survive in the nooks and crannies of a world rapidly being taken over by our own more powerful civilization.” She goes on to assert that humanity should treasure all cultures, especially those still living in ways of being and thinking in harmony with the natural world. “Some day we may need it,” she adds.

Hold that thought. I did.

The other treasured book I read and reread in tandem was A Wrinkle in Time, published in 1962.

These two books spoke to me because from an early age I was good at math and science, precociously so, but also had a sensitivity to the natural world of animals and trees and rocks that was intuitive and mystical rather than scientific. Both books held a regard for the common good, for valuing contributions from individuals who think and look differently - certainly different from what was the norm of my mainly middle class, mainly college educated, mainly white world.

The parents in A Winkle in Time were scientists, but the whole family becomes deeply involved, with unexpected allies, in a battle for the soul of the world. I was young, but I felt a deep calling to join in that battle, which I knew was real.

Hold that thought. I did.

These themes of indigenous thought and non-religious spirituality played out in 1974-75, my senior year in college at the University of Colorado-Boulder (if you are doing the math and wondering, I skipped a few grades and graduated five weeks after my 19th birthday).

First - in a rebellious moment, I decided to meet my “foreign” language requirement with two semesters of Lakota. Entering the classroom, I was shocked to be the only wasicu (white person) in a class of Native students intent on regaining the language their parents had lost. Intimidating as it was at first, I persisted. Eventually I was invited to their parties and their Red Power/AIM rallies. I became a friend and an ally.

The professors were linguists, assisted by a graduate student named Eli James, a native speaker from Pine Ridge. The professors taught us Lakota vocabulary and grammar, but from the perspective of linguistics, introducing us to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Sapir and Whorf proposed that language shapes the ontological and epistemological framework of the speaker. In other words, the language in which we learn about and describe the world shapes our perception of it. Language shapes what we understand to be the nature of the world, and how we decide what is true.

This was the conceptual insight I brought to my reading in 1974 of the newly published Beyond God the Father. In feminist theologian Mary Dalyʻs prose, I found an explanation for why I was not drawn to the Judeo-Christian tradition. It was language! I did not see myself in the language of the Bible, it did not match my perception of the world nor my hopes for the life I was intent on living. I sought out Dr. Doris Havice, Chair of the Religious Studies Department. I shared my insight and inquiry, begging her to offer a course on Women and Religion in the spring semester. It would be both my last semester on campus, and her last semester as she was reaching the mandatory retirement age of 68.

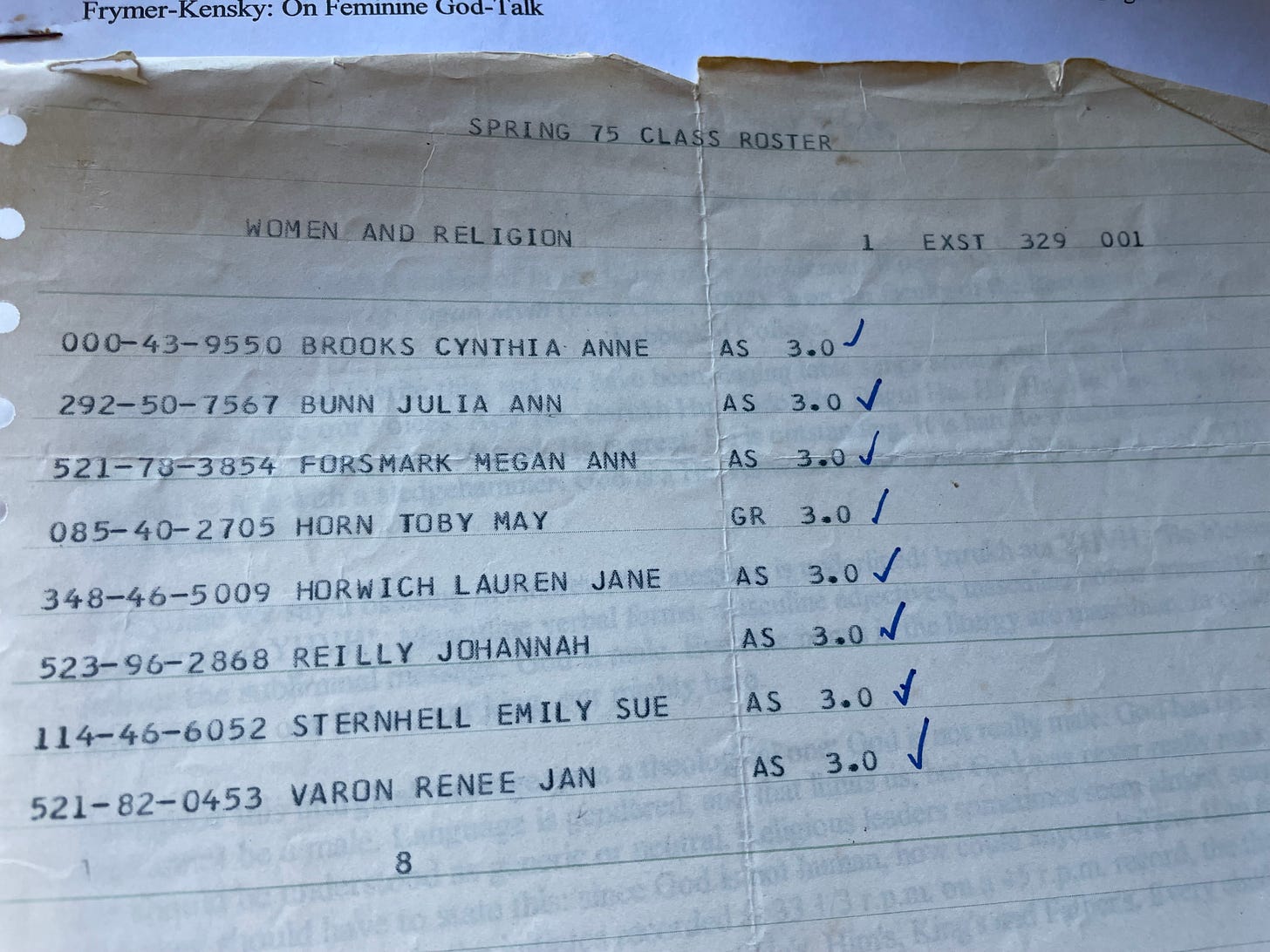

After hours of conversation, Doris offered me an alternative. Any member of the campus community could propose a course to the Experimental Studies program, and if accepted it would be offered for college credit. Under her mentorship I wrote a syllabus, and then taught a course called Women and Religion: The Blossoming of Feminist Theology, co-listed with the Women Studies Program. Seven women and one brave man registered for the course.

An eighteen-year-old honors student, majoring in mathematics just because that was the easiest thing to do, deep diving into indigenous thought and womenʻs spirituality.

Hold that thought. Because for fifteen years I forgot.

From here on in this memoir, we jump through a wrinkle in time to the years 1990-1994.

Newly divorced from my first husband, I spent Christmas 1989 with my BFF, her husband, and my goddaughters in Mexico. The divorce was a mutual, respectful undertaking and I felt more excited than sad at the prospect of a new life ahead. In lieu of New Yearʻs resolutions, in January of 1990 I asked myself “What are the top five things you have always said you wanted to do and have not done? Why havenʻt you done them?”

“Why havenʻt you done them,” was a rhetorical question. They were not part of the married life we had shared, a life in which I had grown and thrived in many ways. But the parts of me that I had left behind for fifteen years were tired of waiting for me to notice.

The five things I wrote were:

Learn to ski (black diamonds)

Trek in the Himalayas

Live abroad and learn another language and culture

Buy art from artists who are friends

Learn about life from an Indian medicine woman.

As it turned out, the first item on the list was only there because I was envisioning a life with the man who was my transitional relationship. Skiing was his passion, not mine. I could ski downhill, poorly. I could ski cross-country like a maniac. I just did not like having to be around so many people in long lines, freezing at a ski lift. I much preferred the quiet swish of my skis in the wilderness, sometimes even heading out after morning classes during graduate school for a few hours of solitary communion with Nature. Scratch skiing.

Learn to ski (black diamonds)

Within a year, and without effort on my part, the four items that mattered were already manifesting. By 1992, all four would come to fruition, and I was leaving behind the transitional relationship. That was painful, as my poems from 1992 bear witness, but necessary. It would have been an even less suitable partnership than my marriage for the person I was becoming.

And that is what happened before what happens happens.