Welcome to my new readers and subscribers, and welcome back to those of you who have been here before. I still have questions - top among my many questions - the question of what brought you here and since “they” keep telling me I should write, the question of what it is the They that is You would like the Someone who is Me to write about. If any of you would like to share, comments are open.

Also, so far no one has yet written answers to even what I thought were my easiest questions. So while Iʻm asking, maybe someone can tell me…

Is the iPhone 15 worth it?

Are skinny jeans really not cool anymore?

Finally, if by some odd chance you found your way here without subscribing and would like to get essays from me weekly, feel free to enter your email address in the box below. And I do mean feel FREE because it is. Free.

And now back to the serious stuff.

During the past month I pondered the nature of good work in Are You Ashamed of Your Profession, followed by But is Work as Self-Development Selfish, and But what About My Personal Legend. I thought I came to the end of my Yeah Buts on good work and could move on this week. Then my inner observer started kicking me, little under-the-table-get-your-attention nudges. What I observed was my inner judge judging me for judging myself. Gulp. Not only do I judge myself, but I judge myself for doing it! Thatʻs so harsh. I canʻt get away from being human, an absolute assessment machine, a limbic system always trying to figure out whether I am doing what I need to do to find safety and connection and love in this moment in which I find myself.

Or maybe itʻs just the Season, bringing a secret worry I never shook. Santa is tallying up my deeds for the year as naughty or nice.

I am clearly attached to the outcome of my work, and maybe to “Santa” - those external assessments of the goodness of my work. But is being attached to either of those concerns possibly a good thing? Isnʻt all attachment a not-good thing? Thatʻs the source of the self-judgment in my mind.

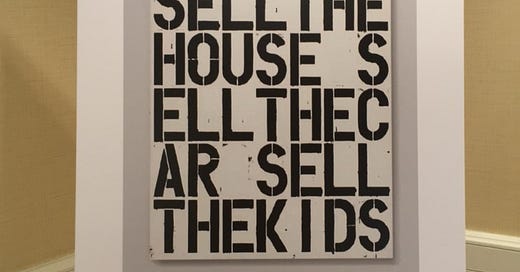

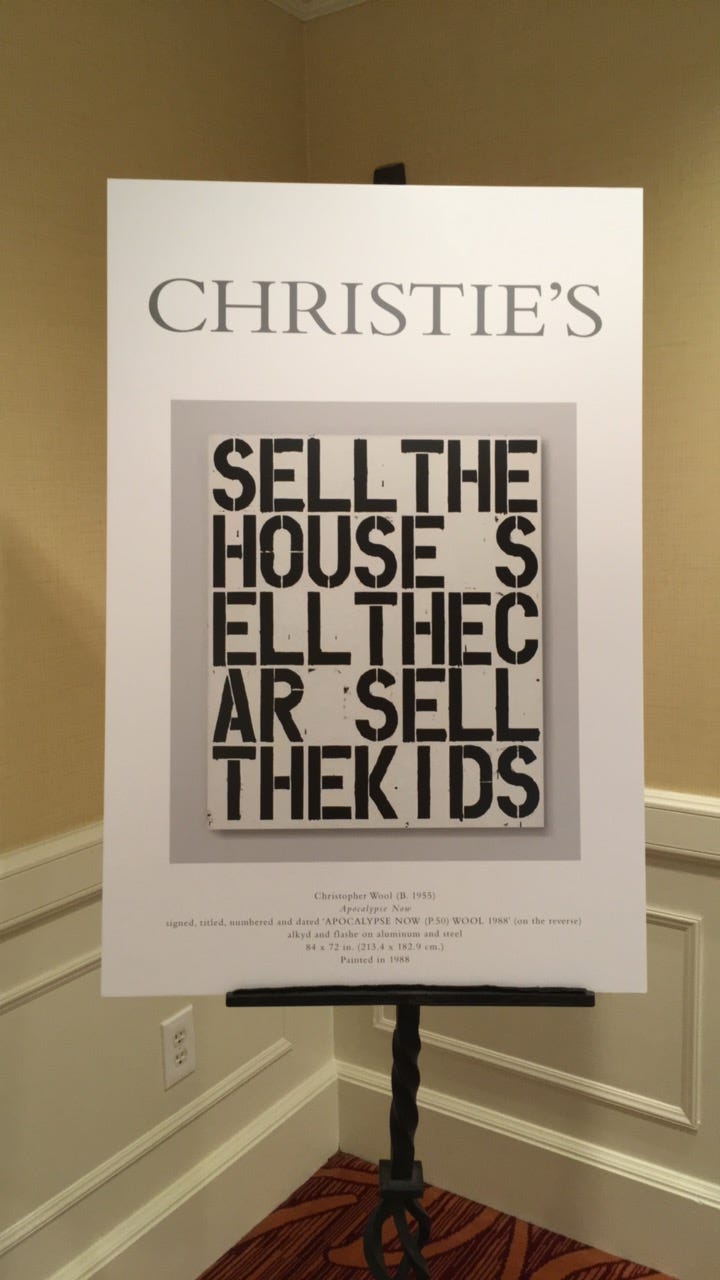

In this business of being a good person, it is hard to be a householder rather than a monk. Maybe I should just sell everything and don robes.

Where do these standards come from? And why do I worry about having them? I wrote in this memoir about finding my way to Buddhism and a meditation practice in 1992 - a crazy story of how fulfilling a bucket list item of trekking in the Himalayas showed up instead as a journey to Tibet with the personal trainer equivalent of a spiritual teacher. Thirty years. Thatʻs how long I have been working with a framework of being in service to equity and enlightenment for all, and with the concept of non-attachment as a beneficial orientation.

Non-attachment is key to Buddhist thought - a recognition that attachment to situations or people being a certain way, or attachment to material things, or even attachment to our ideas and beliefs, is what creates unhappiness or suffering. Because the only constant in this world is change and that truth hurts us when we resist it being so.

When I notice and become critical of my self-criticism, it is because I despair of my inability to shake my attachments. Usually they are unimportant, like my attachment to how I looked and felt when I was younger, face free of wrinkles, buns of steel. Thirty years of meditation and still I am capable of judging myself harshly about minor things over which I have no control - and then rather than be kind to myself I judge myself for judging.

On the flip side, it is true what they say about getting older. I used to really care a lot about whether other people thought I was a good person, doing good work. Now I have at least figured out that the people who agree with me on whatever my current standards are for those things will think I am a good person doing good work and the people whose standards are different will think I am not, and I have no control over that. But this inner judge is still nagging me about whether I am measuring up to my own standards. And so, for four essays now, I dragged all of you along with me in my attachment to the question of good work, a question which is ultimately asking whether I am a good person, a person I can like and admire. At age 67, I still want to create value and to be valued - and apparently I have high standards for that.

I have been re-reading Kitchen Table Wisdom, a 1996 book by Dr. Rachel Naomi Remen. It is a beautiful collection of lessons on the nature of healing told through stories, small vignettes she heard in counseling both people with life-threatening or chronic illnesses and also the medical professionals who attend them. A number of current circumstances drew me back to her book, things that make me feel sad or worried right now. The fiery destruction of Lahaina in August and the long healing journey survivors are on, individually and as a community. Two close friends receiving cancer diagnoses. A family member dealing with the trauma of a mass shooting incident. The latest news from Gaza.

Coming back to this book after decades, I found many stories I had not remembered. Not coincidentally as I sit in this self-inquiry, I noticed the second section of the book is titled Judgment. Remen introduces the topic with this sentence, “The Life in us is diminished by judgment far more frequently than by disease.” Thatʻs it exactly. It is not the attachment itself but the self-judgment that diminishes me.

Since Kitchen Table Wisdom is after all a book about pathways to healing, as a healer Remen offers both a diagnosis and a cure. In a later section she writes:

Sir William Osler, one of the fathers of modern medicine, is widely quoted as having said that objectivity is the essential quality of the true physician. What he actually said is different and far more profound than that. The original quote was in Latin and it is the Latin word aequanimatas which is usually translated as “objectivity.” But aequanimatas means “calmness of mind” or “inner peace.”

Bingo!

One of the key teachings of Buddhism that inspires me is that on equanimity - the quality of mind and being that is the antidote to all attachment and suffering.

Equanimity is one of the most sublime emotions of Buddhist practice. It is the ground for wisdom and freedom and the protector of compassion and love. While some may think of equanimity as dry neutrality or cool aloofness, mature equanimity produces a radiance and warmth of being. The Buddha described a mind filled with equanimity as “abundant, exalted, immeasurable, without hostility and without ill-will.” - From the transcript of a talk by Gil Fronsdal, May 29th, 2004 on the Insight Meditation Center website

Shoots, it started out ok but as soon as I read “abundant, exalted, immeasurable, without hostility and without ill-will” I immediately started judging myself again, cataloging the dozens of moments in which I had failed in the pursuit of equanimity in this single day alone! Give a girl a break. Still, when I tune into the actual feeling of equanimity, which sometimes I do achieve, I can laugh and be gentle with myself.

It is not a bad thing to have spiritual aspirations, or even, according to the good doctor, a professional duty to aspire to self-development, to achieving calmness of mind and inner peace. At the end of the day, I have come right back to square one. To all honest work being good work because whether paid or unpaid, every moment we interact with others - or act with consequences for others - is a moment that allows for us to cultivate wisdom, freedom, compassion and love.

I write these words at the Winter Solstice for those of us in the northern hemisphere. The longest of the dark nights, literally, and for many, emotionally and metaphorically. For those of you celebrating holidays or the turning of the season in whatever fashion, may you find peace in the depths and inspiration in the light. And the equanimity to have no preference between the two.

Thank you for this beautiful offering. It resonates so deeply with me.

Re skinny jeans:

Focus only on what makes you feel pretty and wonderful and full of charisma - THAT is what’s in fashion! Several years ago, before the Mari Kondo craze and after my second divorce, I went through my drawer of panties and threw out all the ones that didn’t make me feel like a complete vixen. It’s one of the best things I ever did and still do.